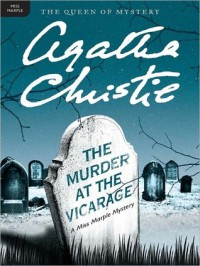

"The Murder At The Vicarage" is a sparkling virtual locked room mystery, filled with benevolent humour and illuminated by the first appearance of the formidable Miss Marple.

Perhaps it's because I've only seen Miss Marple in TV series and in films but I expected her to be in the first scene in her first book, perhaps doing something punitive to delinquent plants in her garden while noting, out of the side of her eye, the arrival of a strange car at the vicarage.

I was completely wrong and I'm delighted to have been so.

The first scene opens with the primary narrator of the story, a rather put upon Vicar who is regretting marrying a very pretty woman, twenty years his junior and who lacks any of the qualities appropriate to a Vicar's wife, pondering the appeal of the celibate life and trying to remember why he married this pretty young woman after knowing her for only twenty-four hours.

When the Vicar asks his wife, Griselda (a startlingly inappropriate name for such a spirited woman), how she'll be spending the day, her reply triggers a wonderful foreshadowing of the presence of Miss Marple:

"My duty as the Vicaress. Tea and scandal at four-thirty"

“Who is coming?”

Griselda ticked them off on her fingers with a glow of virtue on her face.

‘‘Mrs Price Ridley, Miss Wetherby, Miss Hartnell, and that terrible Miss Marple.

’I rather like Miss Marple,’ I said. ‘She has, at least, a sense of humour.’

‘She’s the worst cat in the village,’ said Griselda. ‘And she always knows every single thing that happens—and draws the worst inferences from it.’

Griselda, as I have said, is much younger than I am. At my time of life, one knows that the worst is usually true.

I love the economy of effort and density of humour of this opening.

I rather like the vicar. He's an intelligent, educated, observant, gentle man, not nearly as conventional as he believes his calling requires him to be yet he has preserved an innocence of spirit quite remarkable in a man of his age.

This, of course, makes him the perfect narrator, someone equipped to observe and understand what is going on while having little inclination to participate and an established habit of hoping for the best.

To give you a flavour of the man, take a look at his encounter with a young woman with the extraordinary name of Lettice, (which span my mind off into pointless speculation as to whether she has a sister called Kale or a brother called Chard), The vicar’s interior monologue is:

Just when I was really settling down to it, Lettice Protheroe drifted in.

I use the word drifted advisedly. I have read novels in which young people are described as bursting with energy—joie de vivre, the magnificent vitality of youth … Personally, all the young people I come across have the air of amiable wraiths.

When I finally met Miss Marple at the foreshadowed "tea and scandal at four-thirty", I was not disappointed.

At one point Miss Marple appears to be suggesting that her hostess, Griselda, is the one most likely to be having an affair with a young artist who is painting her. Actually, the example Miss Marple cites suggests that the artist is having an affair with a different married woman. I think Miss Marple knew she could be misunderstood and was playfully pressing Griselda's buttons. Unfortunately, the vicar took the assault at face value and rose to give a spirited, charming and quite ineffectual defence of his wife's honour. This results in afternoon tea closing with some words from Miss Marple and a reflection from the vicar.

‘Dear Vicar,’ said Miss Marple, ‘You are so unworldly. I’m afraid that observing human nature for as long as I have done, one gets not to expect very much from it. I dare say idle tittle-tattle is very wrong and unkind, but it is so often true, isn’t it?’

That last Parthian shot went home.

I admire the precision of Miss Marple's rebuttal of the vicar's exhortations. It reveals a mind more prone to insight than empathy. I love the image the gentle vicar summons up of Miss Marple as a fierce warrior, feinting retreat while turning on her horse and firing an arrow with deadly accuracy. I suspect that, as I read the Miss Marple books, I will often be drawn back to that image.

Most of the time, the people in St Mary Mead in 1930 seem to be very similar to the people I would meet in a village today. Every now and again though, I became aware of differences in reference points that mean I'm probably not seeing the same thing that Christie's readers would have seen. Take, for example, the rather transparently named Mrs Lestrange, about whom the whole village is speculating. Having been invited into her house, the vicar considers Mrs Lestrange and is unable to escape the impression that she is other than she seems to be. He finds himself wondering:

...more and more what had brought such a woman as Mrs Lestrange to St Mary Mead. She was so very clearly a woman of the world that it seemed a strange taste to bury herself in a country village.:

This left me struggling to decode "so very clearly a woman of the world".

What is "a woman of the world" and what is it about Mrs Lestrange's behaviour, presentation or conversation that makes it so clear that she is one? I feel in need of a native guide or an historical anthropologist or perhaps a learned footnote.

Of course, there is more to "The Murder At The Vicarage" than charming characters. What makes the book a classic is the way in Agatha Christie structures her novel. Where another author might have been satisfied with weaving a bread cloth from the interaction of characters and circumstance to set up a mystery, Christie creates an intricate piece of lace from the first page, filled with patterns and motifs and fine detail carefully arranged.

I was told that "The Murder In The Vicarage" was a locked room mystery. I didn't understand this at first, as the murder happens in a room that is not locked. About halfway through the book, I realised it was a locked room meta-problem: a room that can't be reached without being seen yet where no one was seen. That the premise of the story is a meta-problem made me wonder if Agatha Christie had an interest in maths. I've been told that she did and I think Miss Marple is a sort of mathematical detective. At one point, Miss Marple defines intuition as a problem-solving technique that sounds a lot like heuristics.

"Intuition is like reading a word without having to spell it out. A child can’t do that because it has had so little experience. But a grown-up person knows the word because they’ve seen it often"

Towards the end of the book, when Miss Marple is using the vicar as a sounding board for her ideas, she sets out a fairly rigorous set of proofs that need to be satisfied before she is willing to stand behind the ideas she has on who the murderer is.

Another reason I think this book is a classic is that the plot is so clever. When I knew who had done what, I was not surprised. Everything made sense, but only with the benefit of hindsight. While the story was unfolding, I changed my mind many times on who had done what to whom and why. Agatha Christie didn't cheat but she led me through a maze of mirrors that had me jumping at shadows.